Boris Kavur [1]

University of Primorska

Faculty of Humanities

Department of Archaeology and Heritage

Koper, Slovenia

Abstract: Slovenian archaeology, like any other archaeology, was mostly concerned with ceramics. This is through the analysis and publication of large quantities of fragments and entire prehistoric vessels, to which we have narrated typological and chronological characteristics. On the other hand, archaeologists have always been afraid to cross the line between rational archeology and the less rational field of aesthetic evaluation of ceramic decorations. Already in the post-war period, Josip Korošec in his school outlined a number of fundamental features of understanding the technologies of decorating vessels, motifs of decoration and compositions of the latter into larger artistic narratives. It was an approach that was perfected by Tatjana Bregant and represents in its time and context one of the interpretive highlights of Slovenian prehistoric archaeology. At the end of the 20th century, with the standardization of the understanding of the production and design of ceramics, as set forth by Milena Horvat, strict rationalism replaced the soft logic of the aesthetic evaluation of the creative potential of former artists, as it could be recognized in the complexity of the decoration of prehistoric ceramics. Many publications of both systematic and protective excavations unfortunately represent the impossibility of achieving the standard of technological and aesthetic systematic description, as outlined long ago by Korošec. Some modern analyzes have shown the potential for the modern development of the analysis of the decoration of vessels, whereby, in addition to the aesthetic value of the latter, they observed the position on parts of the vessels and the potential of the analyzes of decorations for precise chronological studies. However, to a greater extent, we are still missing precise descriptions and analyzes of individual vessels, analyzes that would allow us to more precisely understand the perception of the physicality of ceramics as well as the culturally specific possibilities of varia bility of decoration and thus provide an insight into the creative potential of prehistoric artists.

Keywords: prehistoric art, pottery decoration, ornaments, material culture, hi story of archaeology

INTRODUCTION

This reflection does not attempt to be objective, as the result of my personal involvement in the problematic, my personal frustration with the subject and my personal perspective of reading about pottery decoration, the text is highly subjective. And since I do not believe that the practice of archaeology is purely a matter of bringing to light sources/material and putting it in to order (and taking care for it) my attempt is to stress the highlights and to start the discussion that might eventually culminate in a major analysis of this subject that would not only evaluate the past approaches, rhetoric and assumptions, but would also suggest how to optimally understand an important constructive element of history of Slovenian archaeological thought. It will focus on a selection of approaches dealing (or actually not at all) with decoration of prehistoric pottery – an omnipresent, but only rarely addressed problem in Slovenian archaeology. Although mostly considered as being a part of crafts, rather than art, it is my deepest believe that the ornaments were not executed without much imagination or care. And if most theories of style in archaeology, developed in the last half of the century, have in common the justified true belief that the decoration of artifact forms such as pottery can be a cost-effective means of sending culture-specific messages (David, Sterner & Gavua 1988), I am afraid that such a perspective is almost completely missing in the habitus of doing archaeology in the region.

PROBLEM OR SOLUTION

When speaking the beginning of Slavic or Early Medieval archaeology of Slovenia, it was always stressed the importance of the excavations of Josip Korošec conducted on Castle hill in Ptuj and its subsequent publications of the results (Guštin 2017). But when we are considering the beginning of prehistoric archaeology, and within the field of detailed analysis and description of ornamentation on the pottery, we also have to return to the same historic events. Beside his poetic style of description, it was Korošec that, in the publication of prehistoric finds, clearly defined the techniques of decorations setting the frameworks for understanding of the problem. Further he, in the detailed description of every technique used, described the motives and compositions of them that were produced with this technique and included references to the items depicted in the catalogue. In this way he linked the occurrences of individual motives to specific pottery forms that were subsequently analyzed in a chronological and cultural context (Korošec 1953: 123–141).

The publication of finds from the Castle hill in Ptuj were just the beginning of the approach that produced magnificent publications and discussions of decoration, this is ornaments, motives and compositions, on prehistoric, mostly Neolithic pottery. Perhaps the most important publication of this approach was the book on the Neolithic finds in Danilo Bitinj in Dalmatia published by Josip Korošec just a few years later (Ko ročec 1958). There again he clearly distinguished the ornaments according to techniques used and motives produced. While discussing the techniques used in decoration he linked them to the specific forms of vessels and stressed the positions of ornaments on them (Korošec 1958: 72, 76).

But when looking at the motives, being so numerous and variable at first glance, he concluded in his analysis that the motives are following only a limited set of compositions created by these motives (Korošec 1958: 76 – 83). Here he introduced in the discourse detailed descriptions of the motives as well as the aesthetic evaluations of their structuring in terms of symmetry and continuity on the pottery, but also focusing on the relations between the decorated and undecorated parts of the pots. But most important, to highlight the aesthetic complexity of the motives depicted, he reproduced a series of idealized reconstructions of motives (Korošec 1958: 78–88, pic. 12–17). With this approach he paved the road that lead to the publication of the most important discussion on prehistoric art and creativity, focusing on pottery ornamentation – the book Ornamentika na neolitski keramiki v Jugoslaviji that was published in 1968 by Tatjana Bregant – la grand opus that combined in a reduced for mat the idealistic reconstructions of major motives depicted on pottery from numerous sites from different Neolithic cultures from a vast territory. With this publication, as mentioned by the author in the introduction, the ornamentation of pottery was elevated to the prime form of Neolithic artistic production (Bregant 1968).

The major problem of the book was that it was published in Slovenian language and despite the fact, that it was as a standard manual for the understanding of Neolithic and often referred to, it was the numerous plates with the depictions of individual motives from sites and cultures that were observed, while the text was only rarely properly understood. The other basic assumption, that might with the modern dating techniques be proven as erroneous, was the belief in the evolutionary development of motives from the most basic to the most complex. A notion that was in decades to follow underlying the assumptions of development of subsequent chronological phases in numerous Neolithic cultures. Looking at the complexity of Neolithic decorations she even concluded that the development of complex motives was faster than the ability to combine them in new and complex compositions and, according to her opinion, it was the recognizable and repetitive combining of techniques, motives and compositions that constituted a style of pottery ornamentation (Bregant 1968: 37–38).

It was almost contemporary that another contribution to the understanding of cultural history, based on detailed and systematic description of pottery, following the standards of the time, was published – the publication of settlement finds from the pile-dwellings near Ig by Paola and Josip Korošec (Korošec & Korošec 1969). The division of the material into two culturally distinctive groups was based on the typology of the pottery but also on its ornamentation that was described as being “extraordinary opulent” and numerous. Still the focus was on the ornamental techniques that were recognized being different while the description of the motives by themselves would not, at least in the rhetoric used by the authors, demonstrate a major difference between the groups (Korošec & Korošec 1968: 15–17). But the major visionary contribution of this publication, although its potential was never properly used, was the idealistic reconstruction of numerous decorations executed in white on a black surface, creating an outstandingly clear visual presentation of the motives (Korošec & Korošec 1968: T. 120–142). Reduced to its artistic essence this demonstration of prehistoric visual creativity was in the catalogue ascribed to individual chronological and cultural phases (Ig I and II) (Korošec & Korošec 1968: 141), but unfortunately not linked to individual pieces of pottery from which it was derived.

Perhaps the last major work on prehistoric pottery, building on the tradition of the school of research founded by Korošec was the book Kultura kolišč na Ljubljanskem barju published by Zorko Harej (Harej 1986). Despite his poetical rhetoric in the introduction of the problem, he correctly approached the problem of decorated pottery and clearly distinguished between the ornamental techniques and the motives in pottery decoration (Harej 1986: 40–43). His systematic introduction and description of major ornamental techniques was for him a tool to search for its origins and define the cultural relations between the material analyzed and several other cultural groups (Harej 1986: 43). Although he reproduced a detailed typology of pottery forms, the ornaments were not presented in a systematic matter.

From the eighties, with the focus of Slovenian prehistoric archaeology shifting to younger periods, the quantity of pottery publications increased. And if due to its long history of research that resulted in the distribution of important discoveries among numerous museums in Europe or the spectacularity of the later or just due to the persistent narrative about its importance, the Early Iron Age of south-eastern Slovenia, from the broader Dolenjska region, is perceived as one of the highlights of past cultural, social and technological development on the territory of todays Slovenia. And despite the fact that the majority of archaeological knowledge was built upon the analyses of material culture from burials, it was the pottery that was the least focused on. In the first, and only book dealing specially with this subject written by Janez Dular (1982), the ornamentation was approached through technology of pottery decoration. The motives were mostly linked to individual techniques of decorations and the later linked to forms of pots and the occurrences on individual parts of them. Following the dominant rhetorical patterns, the author was in the introduction and conclusion lamenting about the poverty of decoration in the discussed region and the lack of studies of the later, expressing the inability to grasp their meaning, but presenting the spatial distribution and chronological precision of “more beautiful” ornaments as satisfying achieved (Dular 1982: 82). Despite the ambitious initial publications the trend was not developed further and the major increase of publications followed only decades later and due to absolutely different factors.

At the end of the eighties the major contribution towards systematic analysis of pottery or at least the development of a clear model of taxonomic description of production technologies, with the definition of geometric proportions describing the forms and attributes. It was created between 1989 and 1999 by Milena Horvat. In her first book, dedicated to the introduction of discoveries in Ajdovska jama, she presented the first approach to the systematic technological and typological breakdown of pottery. Beside the clear description of individual technologies of decoration, it featured also a list of motives present on the pottery (Hor vat 1989: 42–46). The elaboration of the descriptive system developed through the process of education in the next decade culminated with the second book, a manual dedicated to the systematic description of pottery production technology and formal typology (Horvat 1999). The manual was an important general contribution to the standardization of descriptions, clearly presenting the characteristics of different techniques of pottery decorations, although it unfortunately did not motivate the subsequent production of specialized, period/culture-specific manuals that would further elaborate the system regarding the typological variability of pottery production and decoration in a specific period. But it still became the most influential work in terms of terminology used in pottery description. This was mostly due to the fact that it was developed during the educational process conducted by the author at the Department of archaeology at the Faculty of Arts in Ljubljana in the period of the formative phase of most archaeologists that were involved in field research and subsequent publications of results of systematic excavations on Slovenian highways. But the week point of this publication was, and it continues to be, its implementation.

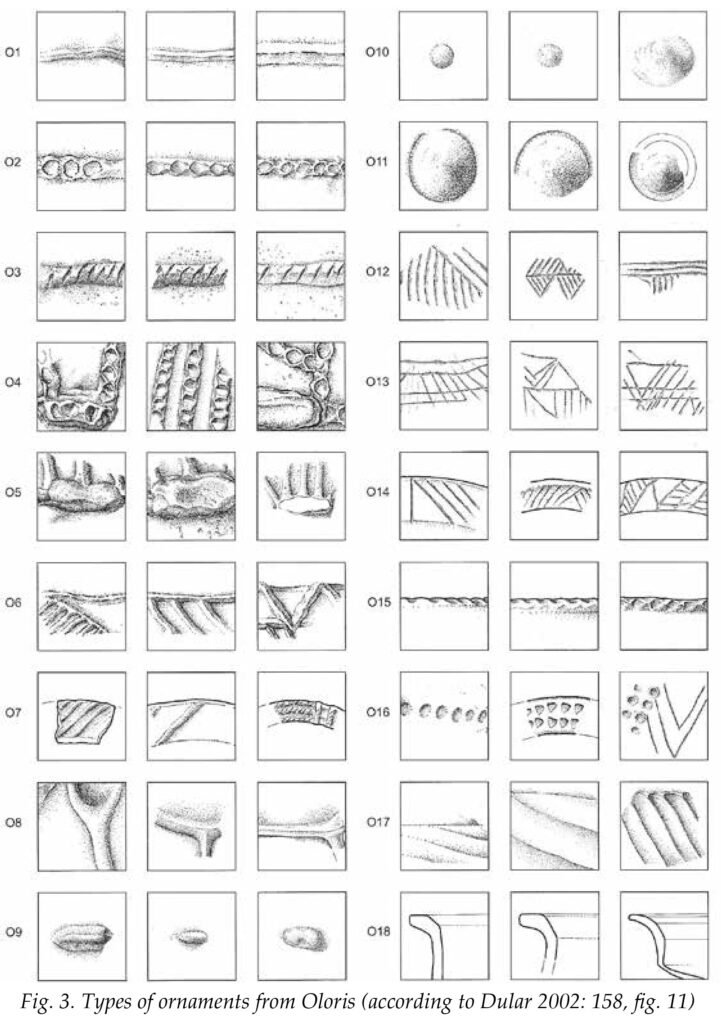

The second publication, that should be mentioned due to its subsequent impact on the methodology of pottery research was the publication of Janez Dular who presented his perspective of a detailed analysis of the discoveries from the Bronze Age settlement of Oloris (Dular 2002). His typological analysis was based, due to the state of fragmentation, mostly on the forms of mouths of pottery and supplemented with two subsequent typological lists – one presenting the grips and handles and the other one the “ornaments” (Dular 2002: 145). Published in the moment when the first books of the highway excavations started to appear the structure of the typology – division of minor fragments into major forms with subforms (that so often resemble too much between different types) became an often-copied approach when dealing with prehistoric pottery. The problem of the approach was and is the identification of boundaries between types of fragmented pottery – the implicit perception that combining all artifactual material (types with sub-types) into a single dataset would create clarification actually led to analytical obfuscation. Unfortunately, here again the confusion of semantic categories was introduced – within the typology of the ornaments are again mixed the techniques and motives, or compositions as the author would call them. For example, oblique hatched incised lines appear in 3 different types of ornaments and applied ribs with triangular cross section even in 5 (Dular 2002: 158, fig. 11). Basically, this approach is documenting the unease with dots and lines – the decoration is typologically subdivided and basically described without being commented. The examples are now focused, they are cut out from existing artifacts instead of being idealistically reconstructed.

The model of presentation and argumentation was further developed a decade later in the publication of selected sites from the Late Bonze Age in north-eastern Slovenia by the same author (Dular 2013). Again, techniques and motives were presented on a table for which miniature decorated fragments of pottery were selected or ornaments were cut out of larger vessels (Dular 2013: 47–60). Even further, ornaments from all three major dis cussed sites, Ptujski Grad, Radgonski grad and Ormož were joined together and based on analogies a chronology of occurrences of different types of ornaments was generated (Dular 2013: 57, fig. 19). The ornaments were used exclusively as chronological information and even in the section when describing exceptional or “foreign” forms the descriptions of ornaments were more than basic (Dular 2013: 58–65). Today, but today is actually two decades long, the majority of Slovenian archaeological publications is focusing on the presentation of pottery. And within this corpus of publications the major part are the excavation reports from the last decades of systematic rescue excavations on the layouts of the Slovenian highway network and the adjacent infrastructure. Although presenting numerous important discoveries, that have changed profoundly our knowledge about the past of the territory of Slovenia and influenced our perceptions of the cultural history of this region, the majority of books were just commented catalogues of pottery that in their methodology of description systematically unsystematically used On the other hand, in the last two decades at least three studies were published where authors, focusing on single sites produced results indicating the potentials for the development of pottery studies and within them the analyses of their ornamentation.

First was the publication of Matija Črešnar presenting several Late Bronze Age graves from Ruše (Črešnar 2006). A detailed typology of pottery forms was followed by a systematic deconstruction of ornaments and their division into 32 motives ranked from the simplest to composed and most complex ones. Important was his correlation of individual motives with pottery forms and their comparison with finds from dated contexts in order to establish their chronology (Črešnar 2006: 132–142).

The second approach to presentation of pottery decoration was produced in the analysis of pottery from the settlement in Stična by Lucija Grahek (Gra hek 2016). Despite some major flow in the composition of the typology, such as the inclusion of pottery from the Early and Late Iron Age on the same typological tables, she was precise and created the primary division based on the ornamentation techniques in which she united the motives produced by later. Despite the lack of 23 description of complex motives, she discussed the correlations between individual techniques, motives and pottery types. (Grahek 2019: 191–220).

The third was the publication of pottery from Čatež – Sredno polje by Alenka Tomaž (Tomaž 2022). Providing detailed statistical analysis of decorated pottery and collection of schematized motives, her major contribution was the detailed analyses of locations of decorations. Demonstrating that similar motives occur on different places and on different forms of pots, she demonstrated the potential of combination of motives on different pottery forms (Tomaž 2022: 66).

PERSPECTIVE

Today we are aware that the aesthetics of an object, especially of a complexly ornamented prehistoric pot, cannot be revealed by a modern assessment of its beauty, because the latter has always been culturally specific and is unfortunately incomprehensible to today’s observer. In our descriptions, evaluations and interpretations we can resort more to the recognition of a specific aesthetic that prehistoric artists produced or reproduced in their works at a certain point in time, in a certain territory – archaeology is mostly today about recognizing and mapping a repetitive form and decoration. But in our interpretations, it should rather be about recognizing the creative potential and innovation that the ancient masters were able to show through the combination of basic motives and techniques used in their manufacture. In most or the pots it should be about the combinations of basic artistic elements, such as dots and lines, their recombination and different orientations as well as also empty spaces between them. Furthermore, it concerns the design of the negative, i.e. undecorated, spaces on the vessel and, consequently, the relationship between decorated and undecorated parts and the principles of their use (Kavur & Ciglar 2021: 342). This means that in our assessment we must observe how the masters were able to assemble individual elements into complex compositions, classify them on the surface of the vessel according to their balance (symmetrical or asymmetrical placement of decorations), rhythmic variation (repetition or replacement of elements that create patterns and effects of depth), proportions (different size ratios between depicted motifs), dominance (visual weight that directs the eye to the first point from which the observer begins to observe the decoration) and the visual unity of the decoration it self (Sofaer 2015: 59). It is, of course, an approach similar to the traditional archaeological definition of style. However, it is more about the principle of the theory of visual perception, when the relationships between form and decoration, between the whole and the individual parts that make it up, are evaluated in the com position (Behrens 1998).

To conclude: how should we perceive pottery decoration and prehistoric art as such? If art is the consequence of hyper-cooperative nature of human communication, based most important on shared intentionality, as developed out of evolutionary pressures due to changing conditions in the environment (physical and social), it needs not only symbolic capacities, but mutual understanding of the coded messages. And the perception of art creates experiences – experiences exist in time and changes over time, they have history. The changes might not be intentional since chance and accident often play a large part in ideas and intentions. These changes create the variability, create the development and evolution of motives, create the multiplicity of experiences only art can mediate. And prehistoric art, in its potential to create abstract visual forms, was most probably (until the 20th century) the most powerful artistic expresion able to display and to perceive embodied cognitive processes.

BIBLIOGRAFIJA

Behrens, Roy R. 1998. „Art, Designand Gestalt Theorie“. Leonardo 31(4): 299–303.

Bregant, Tatjana. 1986. Ornamentika na neolitski keramiki v Jugoslaviji. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga.

Črešnar, Matija. 2006. „Novi žarni grobovi iz Ruš in pogrebni običaji v ruški žarnogrobiščni skupini“. Arheološki vestnik 57: 97–162.

David, Nicholas, Sterner, Judy & Kodzo Gavua. 1988. „Why Pots are Decorated“. Current Anthropology 29(3): 365–389.

Dular, Janez. 1982. Halštatska keramika v Sloveniji. Prispevek k proučevanju halštatske grobne keramike in lončarstva na Dolenjskem. Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti i umetnosti.

Dular, Janez. 2002. „Dolnji Lakoš in mlajša bronasta doba med Muro in Savo“. In: Dular, Janez, Šavel, Irena i Sneža Tecco Hvala. Bronastodobno naselje Oloris pri Dolnjem Lakošu. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, 143–228.

Dular, Janez. 2013. Severovzhodna Slovenija v pozni bronasti dobi / Nordost slowenien in der späten Bronzezeit. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC.

Grahek, Lucija. 2016. Stična. Železnodobna naselbinska keramika / Stična. Iron Age Settlement Pottery. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC.

Guštin, Mitja. 2017. „Ptuj zavzema prvo mesto v staroslovanski arheologiji“. Argo 60(2): 90–99.

Harej, Zorko. 1986. Kultura kolišč na Ljubljanskem barju. Ljubljana: Znanstveni inštitut Filozofske fakultete.

Horvat, Milena. 1989. Ajdovska jama pri Nemški vasi. Ljubljana: Znanstveni inštitut Filozofske fakultete.

Horvat, Milena. 1999. Keramika. Tehnologija keramike, tipologija lončenine, keramični arhiv. Ljubljana: Znanstveni in štitut Filozofske fakultete.

Kavur, Boris i Iva Ciglar. 2021. „Bren gova: Esej o okrasu srednje bronasto dobne amforice“. Zbornik Pokrajinskega muzeja Ptuj – Ormož 7: 333–345.

Korošec, Josip. 1958. Neolitska naseobi na u Danilu Bitinju. Rezultati istraživanja u 1953. godini. Zagreb: Izdavački zavod Jugoslavenske akademije.

Korošec, Paola i Josip Korošec. 1969. Najdbe s koliščarskih naselbin pri Igu na Ljubljanskem barju / Fundgut der Pfahlbausiedlungen bei Ig am Laibacher Moor. Ljubljana: Narodni muzej Slovenije.

Sofaer, Joanna. 2015. Clay in the Age of Bronze. Essays in the Archaeology of Prehistoric Creativity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tomaž, Alenka. 2022. „Čatež – Sredno polje“. Arheologija na avtocestah Slovenije 98. Ljubljana: Ministrstvo za kulturo Slovenije.

PLES TOČKI I CRTA: ZAJEDNIČKA ARHEOLOŠKA NELAGODNOST SA SPECIFIČNIM POGLEDOM NA PRETPOVIJESNU UMJETNOST

Sažetak: Slovenačka arheologija, kao i svaka druga arheologija, najviše se bavila keramikom. To se najprije odnosilo na analizu i objavljivanje veće količine fragmenata i cijelih prapovijesnih posuda, čije smo tipološke i hronološke karakteristike predstavljali. S druge strane, arheolozi su se oduvijek bojali preći granicu između racionalne arheologije i manje racionalnog područja estetskog Ključne riječi: pretpovijesna umjetnost, keramički ukrasi, ornamentika, materijalna kultura, povijest arheologije vrednovanja keramičkih ukrasa. Josip Korošec je već u poslijeratnom razdoblju u svojoj školi iznio niz ključnih aspekata za razumijevanje tehnologija ukraša vanja posuda, motiva ukrasa i njihovih povezivanja u veće umjetničke narative. Bio je to pristup koji je usavršila Tatjana Bregant i koji u svom vremenu i kontekstu predstavlja jedan od interpretativnih vrhunaca slovenačke prapovijesne arheologije. Krajem XX vijeka, standardizacijom shvatanja proizvodnje i oblikovanja keramike, kako ih je postavila Milena Horvat, strogi racionalizam zamjenjuje meka logika estetskog vrednovanja stvaralačkih potencijala neka dašnjih umjetnika, koji su se mogli uočiti u složenijoj dekoraciji pretpovijesne keramike. Brojne publikacije, kako sistematskih tako i zaštitnih iskopavanja, nažalost ukazuju na nemogućnost postizanja standarda u tehnološkom i estet skom sistematskom opisivanju, kako je to davno zacrtao Korošec. Neke savremene analize otvorile su mogućnost za dalji razvoj u proučavanju ukrasa po suda, pri čemu su, pored njihove estetske vrijednosti, uzele u obzir i položaj na djelovima posuda i potencijal analiza ukrasa za precizne hronološke studije. Međutim, i dalje nam u većoj mjeri nedostaju precizni opisi i analize pojedinih posuda, koji bi nam omogućili da bolje razumijemo percepciju fizikalnosti keramike, kao i kulturološki specifične mogućnosti varijabilnosti ukrasa i na taj način pružimo uvid u stvaralački potencijal praistorijskih umjetnika.

Ključne riječi: pretpovijesna umjetnost, keramički ukrasi, ornamentika, materijalna kultura, povijest arheologije

ENDNOTES

[1] boris.kavur@upr.si.

SEPARAT RADA

Separat ovog rada (pdf), objavljenog u prvom broju časopisa Konteksti kulture: studije iz humanistike i umjetnosti, možete preuzeti klinom na ovaj link.